Joshism

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2019

- Messages

- 488

- Reaction score

- 587

Reading yesterday's blog post by @PatYoung I started wondering: how long would it have taken?

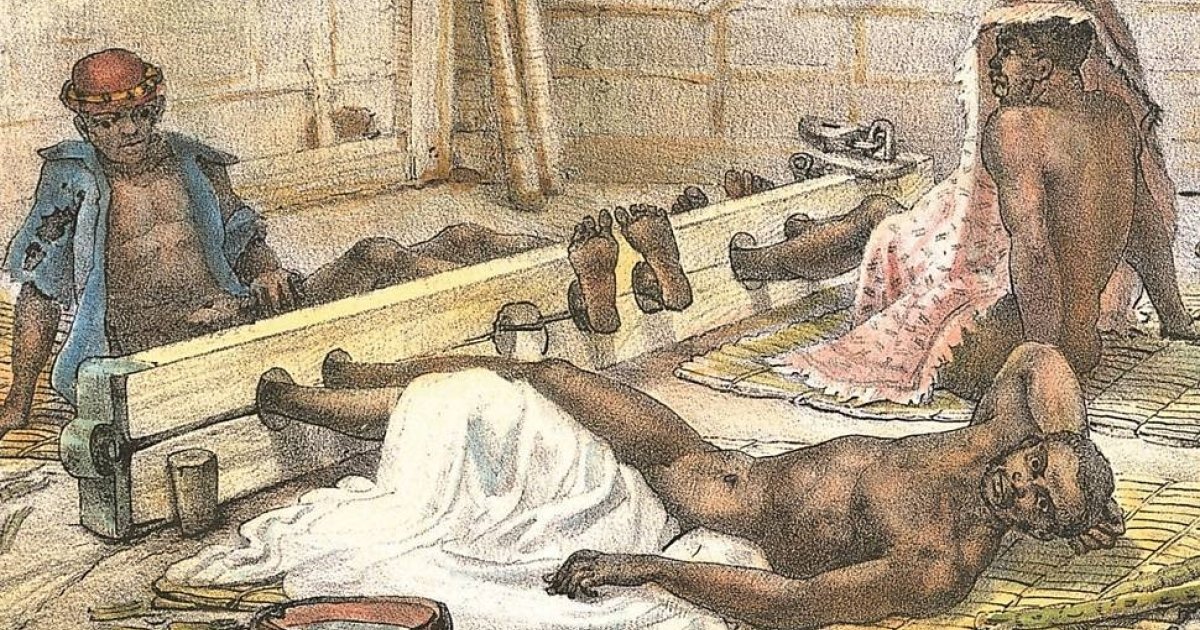

In 1865, the vast majority of white Southerners earnestly believed whites were inherently superior to blacks. They believed various stereotypes about the laziness, barbarousness, etc. of blacks. Their northern counterparts were by no means immune to this, but many had their opinions changed by the USCT, as others would later by the Buffalo Soldiers of later wars on through WW2.

Let us suppose the North had the willpower to enforce some semblance of civil rights in the South for an extended period of time (I don't think they did, but let's imagine). How long would it have taken most of the white Southerners to come around to some semblance of accepting the equality, at least legally, maybe socially, of black and white? A generation? Two generations?

Keep in mind this is without any equivalent to denazification (deslavificiation?) for the South. That isn't simply improbably, but both too ahead of its time to be remotely plausible and the North simply didn't have enough of a morale high ground on the issue to pull it off.

Do we have any frame of reference? Has any another country effectively overcome centuries of deeply-ingrained stratified racism? Is South Africa the closest example? Or maybe the change of opinions about the Irish - from only one step above an African American in much of the public's mindset to everyone loves St. Patrick's Day?

In 1865, the vast majority of white Southerners earnestly believed whites were inherently superior to blacks. They believed various stereotypes about the laziness, barbarousness, etc. of blacks. Their northern counterparts were by no means immune to this, but many had their opinions changed by the USCT, as others would later by the Buffalo Soldiers of later wars on through WW2.

Let us suppose the North had the willpower to enforce some semblance of civil rights in the South for an extended period of time (I don't think they did, but let's imagine). How long would it have taken most of the white Southerners to come around to some semblance of accepting the equality, at least legally, maybe socially, of black and white? A generation? Two generations?

Keep in mind this is without any equivalent to denazification (deslavificiation?) for the South. That isn't simply improbably, but both too ahead of its time to be remotely plausible and the North simply didn't have enough of a morale high ground on the issue to pull it off.

Do we have any frame of reference? Has any another country effectively overcome centuries of deeply-ingrained stratified racism? Is South Africa the closest example? Or maybe the change of opinions about the Irish - from only one step above an African American in much of the public's mindset to everyone loves St. Patrick's Day?

Last edited: