5fish

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jul 28, 2019

- Messages

- 10,771

- Reaction score

- 4,577

For World women's day, I found this Viking woman who travels further than any other woman of her day. She was the first European woman to give birth in the New World. The first nun of Iceland... All foretold to her by her dead husband after rising from the dead... She has a lot of adventures in her travels...

bigthink.com

bigthink.com

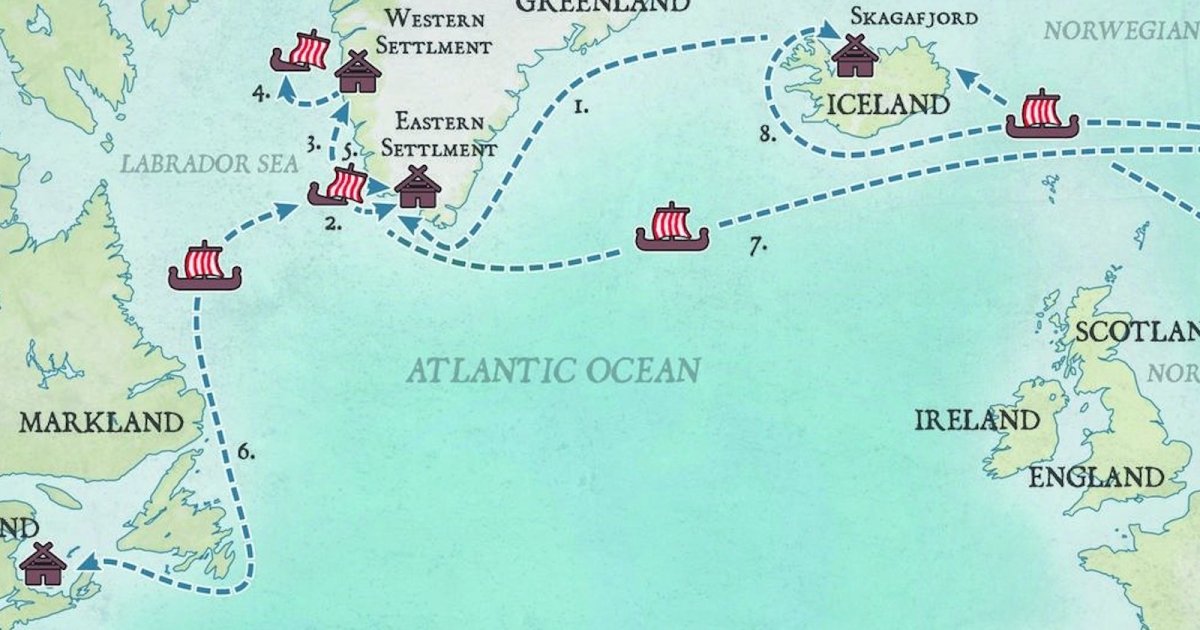

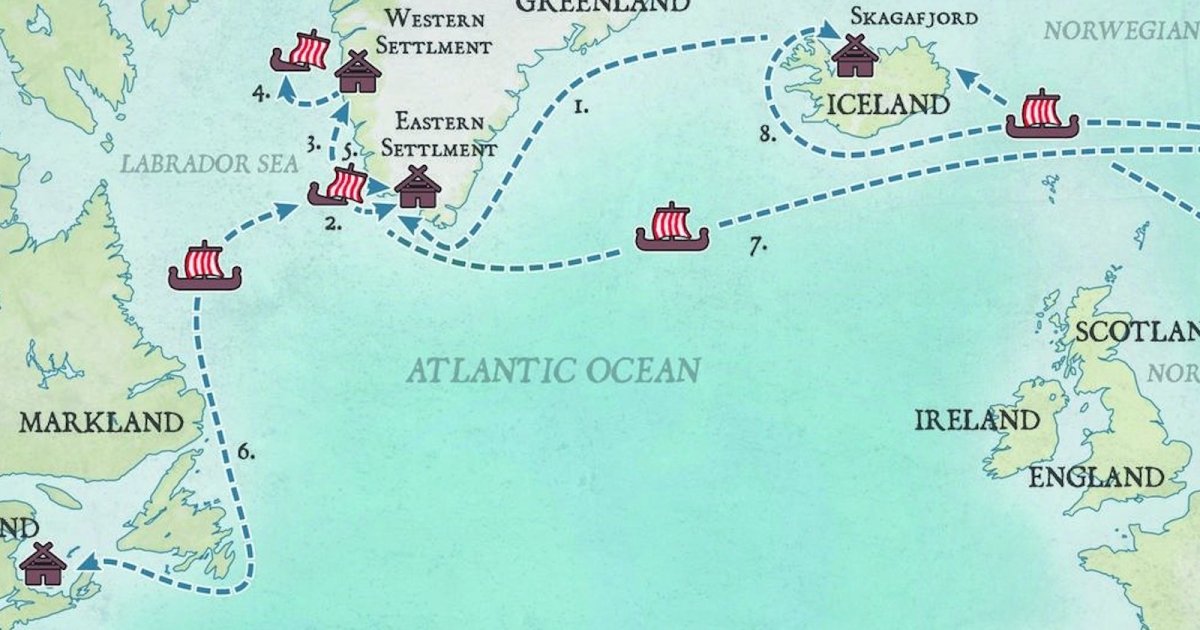

Gudrid the Far-Traveled, daughter of Thorbjorn. She was born around 985 AD on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in western Iceland and died around 1050 AD at Glaumbær in northern Iceland. This map shows the extraordinary extent of her travels in between those dates and places. In all, she made eight Atlantic sea voyages, at a time when those were very dangerous and often deadly

, Gudrid is called “a woman of striking appearance and wise as well, who knew how to behave among strangers.” That’s a trait that may have come in handy when dealing with the Native tribes of North America, whom the other Vikings dismissively called skrælings (“weaklings,” “barbarians”)

Back in Greenland, the newlyweds spend a winter with Thorstein the Black and his wife Grimhild, whose settlement is decimated by a plague. Gudrid’s husband is among those carried off by the disease, but his corpse rises from its deathbed to foretell her future: She will marry an Icelander, with whom she will have many children and a long life; she will leave Greenland, visit Norway, make a pilgrimage south, and return to Iceland.

The family leads a peaceful, prosperous life. Thorfinn dies of old age. When Snorri marries, Gudrid goes on a pilgrimage to Rome (#9), apparently by herself and mainly on foot. When Gudrid returns from her last great voyage to Rome, she finds Snorri has built a church for her, as she requested. Here, she lives out the remainder of her life in solitude and contemplation: the first nun in Iceland, a final achievement in a unique life. It is not known when exactly Gudrid died, but she did not die in obscurity. She established a powerful and influential family.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir (Old Norse: Guðríðr víðfǫrla Þorbjarnardóttir [ˈɡuðˌfriːðr ˈwiːðˌfɔrlɑ ˈθorˌbjɑrnɑrˌdoːtːer]; Modern Icelandic: Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir [ˈkvʏðˌriːðʏr ˈviðˌfœ(r)tla ˈθɔrˌpja(r)tnarˌtouhtɪr̥]; born possibly around 980–1019) was an Icelandic explorer, born at Laugarbrekka in Snæfellsnes, Iceland. She appears in the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders, known collectively as the Vinland sagas. She and her husband Þorfinnur Karlsefni led an expedition to Vinland where their son Snorri Þorfinnsson was born, believed to be the first European birth in the Americas outside of Greenland. In Iceland, Gudrid is known by her byname víðförla (lit. wide-fared or far-traveled).

The Viking woman who sailed to America and walked to Rome

The amazing life of “Gudrid the Far-Traveled” was unjustly overshadowed by her in-laws, Erik the Red and Leif Erikson.

Gudrid the Far-Traveled, daughter of Thorbjorn. She was born around 985 AD on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in western Iceland and died around 1050 AD at Glaumbær in northern Iceland. This map shows the extraordinary extent of her travels in between those dates and places. In all, she made eight Atlantic sea voyages, at a time when those were very dangerous and often deadly

, Gudrid is called “a woman of striking appearance and wise as well, who knew how to behave among strangers.” That’s a trait that may have come in handy when dealing with the Native tribes of North America, whom the other Vikings dismissively called skrælings (“weaklings,” “barbarians”)

Back in Greenland, the newlyweds spend a winter with Thorstein the Black and his wife Grimhild, whose settlement is decimated by a plague. Gudrid’s husband is among those carried off by the disease, but his corpse rises from its deathbed to foretell her future: She will marry an Icelander, with whom she will have many children and a long life; she will leave Greenland, visit Norway, make a pilgrimage south, and return to Iceland.

The family leads a peaceful, prosperous life. Thorfinn dies of old age. When Snorri marries, Gudrid goes on a pilgrimage to Rome (#9), apparently by herself and mainly on foot. When Gudrid returns from her last great voyage to Rome, she finds Snorri has built a church for her, as she requested. Here, she lives out the remainder of her life in solitude and contemplation: the first nun in Iceland, a final achievement in a unique life. It is not known when exactly Gudrid died, but she did not die in obscurity. She established a powerful and influential family.

Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir (Old Norse: Guðríðr víðfǫrla Þorbjarnardóttir [ˈɡuðˌfriːðr ˈwiːðˌfɔrlɑ ˈθorˌbjɑrnɑrˌdoːtːer]; Modern Icelandic: Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir [ˈkvʏðˌriːðʏr ˈviðˌfœ(r)tla ˈθɔrˌpja(r)tnarˌtouhtɪr̥]; born possibly around 980–1019) was an Icelandic explorer, born at Laugarbrekka in Snæfellsnes, Iceland. She appears in the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders, known collectively as the Vinland sagas. She and her husband Þorfinnur Karlsefni led an expedition to Vinland where their son Snorri Þorfinnsson was born, believed to be the first European birth in the Americas outside of Greenland. In Iceland, Gudrid is known by her byname víðförla (lit. wide-fared or far-traveled).