5fish

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jul 28, 2019

- Messages

- 13,795

- Reaction score

- 5,360

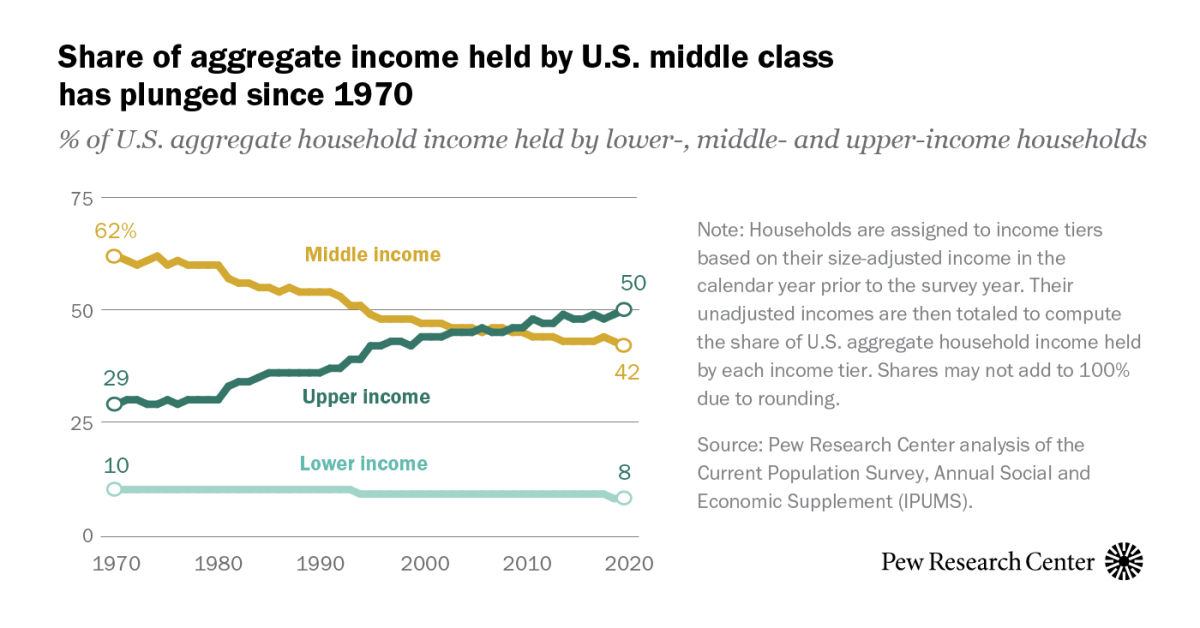

The Free Market can solve all things. Market Fundamentalism is pervasive in Neoliberal economics. In the end like all other aspects of Neoliberalism it breeds inequality and works against the common good.

www.wbur.org

www.wbur.org

“What we're trying to show in the book is how an ideal of the free market in the singular was put forward by business interests in the United States,” Oreskes says, “as a way to fight back against regulation of the workplace, to fight back against people who are trying to limit child labor and to persuade the American people that government regulation of the marketplace was not in our interest.”

“Not too many people today would stand up in public and say greed is good. But people do continue to say that self-interest is good, that self-interest drives entrepreneurs, it drives people to invent things and be creative,” she says. “And that's true up to a point. But we also know that self-interest has to be tempered against the common good, and that when we have inadequate regulation of markets and workplaces, people get hurt

But in the early twentieth century, a group of self-styled “neo-liberals” shifted economic and political thinking radically. They argued that any government action in the marketplace, even well intentioned, compromised the freedom of individuals to do as they pleased—and therefore put us on the road to totalitarianism. Political and economic freedom were “indivisible,” they insisted: any compromise to the latter was a threat to the former—any compromise at all, even to address obvious ills like child labor or workplace injury. Why did we ever come to accept a worldview so impervious to facts? A worldview Smith himself, often thought of as the father of free-market capitalism, would have rejected?

Market fundamentalists, however, depart from Smith by insisting there is no “common good,” merely the sum of all the individual private goods. For this reason, they reject government’s claims to represent “the people”: there are only individuals who represent themselves, and they do this most effectively not through their governments, even democratically elected ones, but through free choices in free markets. Milton Friedman, America’s most famous market fundamentalist, went so far as to argue that voting was not democratic, because it could too easily be distorted by special interests and because in any case most voters were ignorant. But rather than consider how special interests might be mitigated or how voters could be better informed, he maintained that true freedom was not expressed in the voting booth. “The economic market provides a greater degree of freedom than the political market,” Friedman said in South Africa in 1976, as he encouraged the citizens of that country not to fuss over apartheid, but to preserve and expand their market-based economy.

Market fundamentalism perpetuates a mistake in categories, conflating capitalism, which is an economic system, with democracy, which is a political system. We think that the properly framed choice is not capitalism versus tyranny; it is democracy versus tyranny, and well-regulated capitalism versus poorly regulated capitalism. Whether its advocates were cynical or sincere, market fundamentalism has hobbled our response to a host of problems that face us today, threatening our well-being and even the prosperity that markets are designed to deliver. The rhetoric of the magic of the marketplace made meaningful alternatives disappear.

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

In their new book – The Big Myth – How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market – Oreskes and Conway document the rise of what’s more politely called “market fundamentalism” over the last century, from corporate propaganda and fringe academic theory to mainstream ideology.

'The Big Myth' explores the belief that free markets are a fundamental American right

Harvard professor and author Naomi Oreskes co-authored "The Big Myth" with Erik M. Conway.

“What we're trying to show in the book is how an ideal of the free market in the singular was put forward by business interests in the United States,” Oreskes says, “as a way to fight back against regulation of the workplace, to fight back against people who are trying to limit child labor and to persuade the American people that government regulation of the marketplace was not in our interest.”

“Not too many people today would stand up in public and say greed is good. But people do continue to say that self-interest is good, that self-interest drives entrepreneurs, it drives people to invent things and be creative,” she says. “And that's true up to a point. But we also know that self-interest has to be tempered against the common good, and that when we have inadequate regulation of markets and workplaces, people get hurt

But in the early twentieth century, a group of self-styled “neo-liberals” shifted economic and political thinking radically. They argued that any government action in the marketplace, even well intentioned, compromised the freedom of individuals to do as they pleased—and therefore put us on the road to totalitarianism. Political and economic freedom were “indivisible,” they insisted: any compromise to the latter was a threat to the former—any compromise at all, even to address obvious ills like child labor or workplace injury. Why did we ever come to accept a worldview so impervious to facts? A worldview Smith himself, often thought of as the father of free-market capitalism, would have rejected?

Market fundamentalists, however, depart from Smith by insisting there is no “common good,” merely the sum of all the individual private goods. For this reason, they reject government’s claims to represent “the people”: there are only individuals who represent themselves, and they do this most effectively not through their governments, even democratically elected ones, but through free choices in free markets. Milton Friedman, America’s most famous market fundamentalist, went so far as to argue that voting was not democratic, because it could too easily be distorted by special interests and because in any case most voters were ignorant. But rather than consider how special interests might be mitigated or how voters could be better informed, he maintained that true freedom was not expressed in the voting booth. “The economic market provides a greater degree of freedom than the political market,” Friedman said in South Africa in 1976, as he encouraged the citizens of that country not to fuss over apartheid, but to preserve and expand their market-based economy.

Market fundamentalism perpetuates a mistake in categories, conflating capitalism, which is an economic system, with democracy, which is a political system. We think that the properly framed choice is not capitalism versus tyranny; it is democracy versus tyranny, and well-regulated capitalism versus poorly regulated capitalism. Whether its advocates were cynical or sincere, market fundamentalism has hobbled our response to a host of problems that face us today, threatening our well-being and even the prosperity that markets are designed to deliver. The rhetoric of the magic of the marketplace made meaningful alternatives disappear.

‘Market rules should benefit the majority of the citizenry’: historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik M Conway

In their new book, The Big Myth, the authors document the rise of ‘market fundamentalism’ and Americans’ relationship with government regulations

In their new book – The Big Myth – How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market – Oreskes and Conway document the rise of what’s more politely called “market fundamentalism” over the last century, from corporate propaganda and fringe academic theory to mainstream ideology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/investopedia-social-share-default-ab113c8afd9a439dbc4c68b1926292f4.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-155096621-5683321f5f9b586a9efc9f89.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-909192710-5c4d1d204cedfd0001ddb40f.jpg)