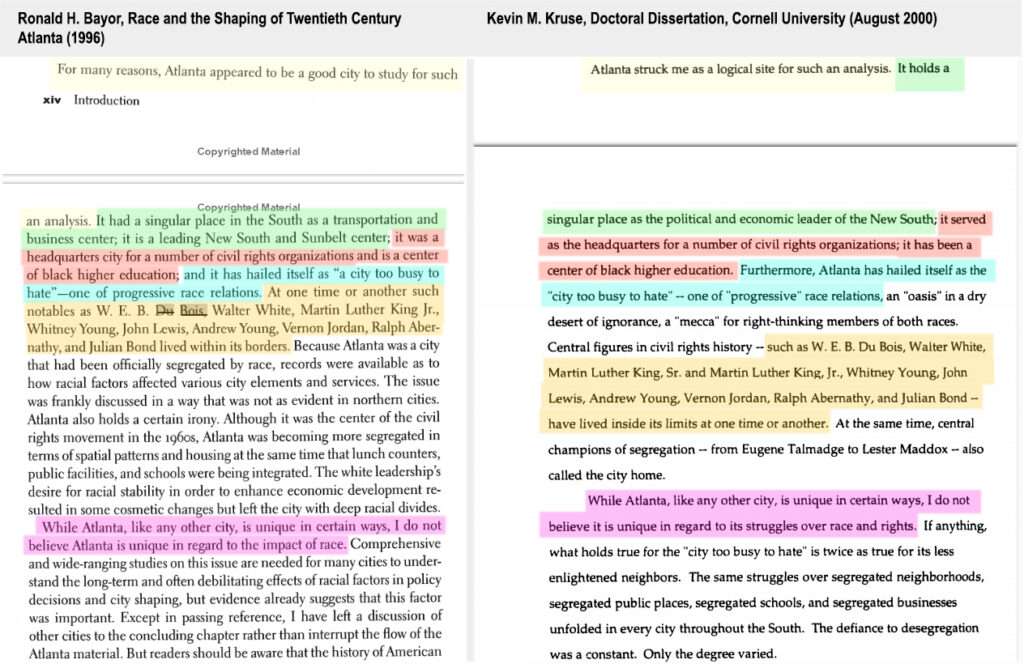

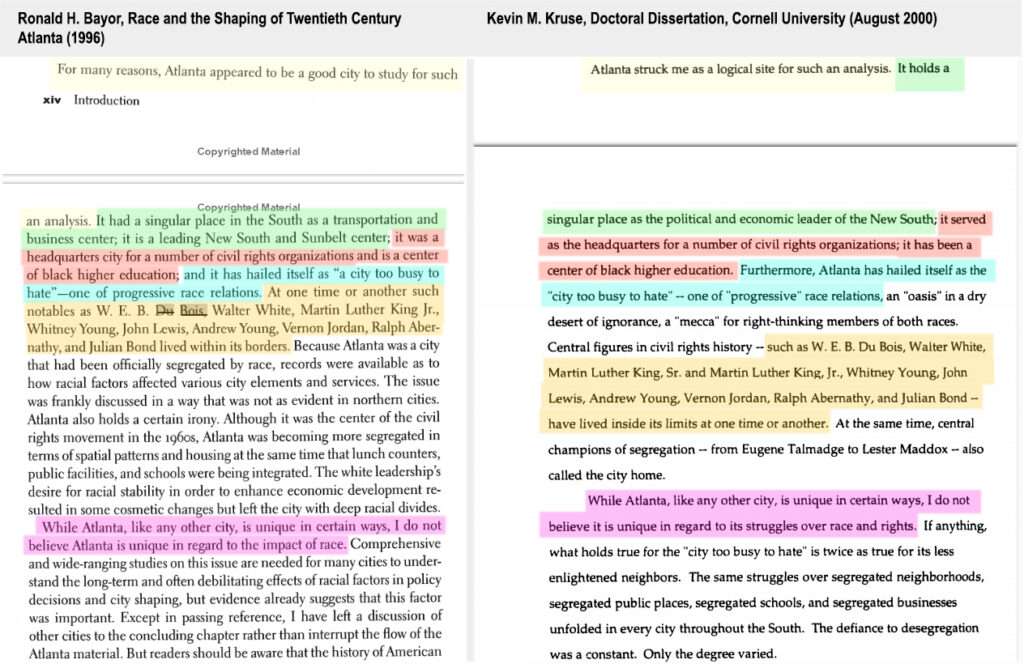

Dr. Phillip Magness accused Professor Kevin Kruse of Princeton University of plagiarism in his doctoral thesis in this article in Reason Magazine. Ignoring the snarky comments and questionable assertions in Magness’s article, let’s get to the actual accusations. Magness writes, “A key passage from Kruse’s doctoral dissertation on the history of race relations in Atlanta displays uncanny similarities to a 1996 book on the same subject by Ronald H. Bayor, a now-retired historian from Georgia Tech. Bayor introduces his academic monograph, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta, by outlining the reasons he chose to study the burgeoning Georgia metropolis: ‘For many reasons, Atlanta appeared to be a good city to study for such an analysis. It had a singular place in the South as a transportation and business center; it is a leading New South and Sunbelt center; it was a headquarters city for a number of civil rights organizations and is a center of black higher education; and it has hailed itself as ‘a city too busy to hate’—one of progressive race relations.’ Compare that to how Kruse introduces his dissertation at Cornell four years later: ‘Atlanta struck me as a logical site for such an analysis. It holds a singular place as the political and economic leader of the New South; it served as a headquarters for a number of civil rights organizations; it has been a center of black higher education. Furthermore, Atlanta has hailed itself as the ‘city too busy to hate’—one of ‘progressive’ race relations.’ “

Magness continues, “The similarities do not stop there. In outlining the background for his study, Bayor provides a long list of Atlanta’s famous African-American residents: ‘At one time or another such notables as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond lived within its borders.’ Kruse’s dissertation repeats the same list, subject only to a minor reorganization of the text: ‘Central figures in civil rights history—such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King, Sr. and Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond—have lived inside its limits at one time or another.’ A few sentences later, Bayor begins to summarize his book’s thesis, writing ‘While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe Atlanta is unique in regard to the impact of race.’ Compare that to how Kruse lays out his dissertation’s thesis, which holds that Atlanta’s experience may be representative of other southern cities in the era of segregation: ‘While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe it is unique in regard to its struggles over race and rights.’ The only difference in this case appears to be a cosmetic change of the last few words.”

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

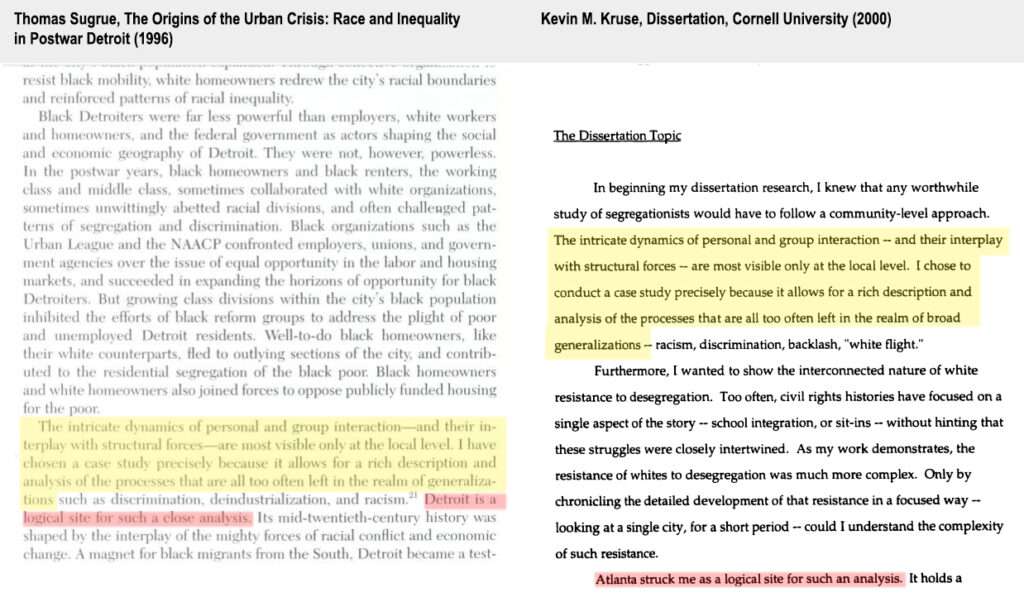

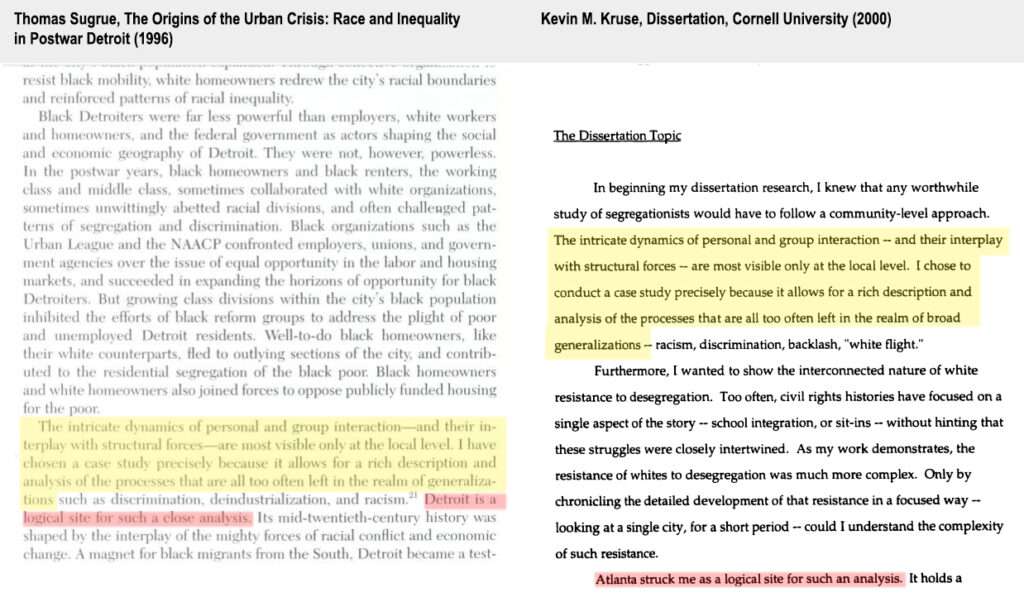

Magness also tells us, “Kruse’s dissertation contains other passages with striking similarities to previously published works. Consider this passage from historian Thomas Sugrue’s 1996 book The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit: ‘The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I have chosen a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of generalizations such as discrimination, deindustrialization, and racism.’ Kruse uses almost identical language in his dissertation, although he shifts its location from Detroit to Atlanta: ‘The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I chose to conduct a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of broad generalizations—racism, discrimination, backlash, ‘white flight.” “

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

According to Magness, “Unlike Clarke, whose masters’ thesis merely failed to place the cribbed but cited texts in quotation marks, the suspect passages in Kruse’s dissertation offer no accompanying footnote to Bayor or Sugrue’s works. His first acknowledgement of Bayor comes several pages later, in a section on the historiography around Atlanta’s civil rights struggles. Here Kruse calls the 1996 book the ‘most impressive work on Atlanta’s race relations’ to date, although he then dings it for focusing ‘solely on the top levels of society.’ (‘Bayor’s work fails to go any deeper,’ Kruse adds. ‘I wanted to show the rest.’) The first reference to Sugrue is an unrelated footnote some 90 pages later in the dissertation.”

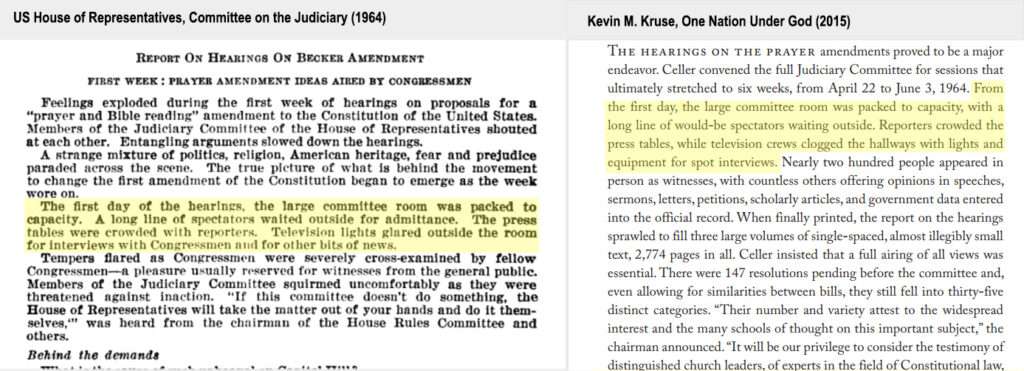

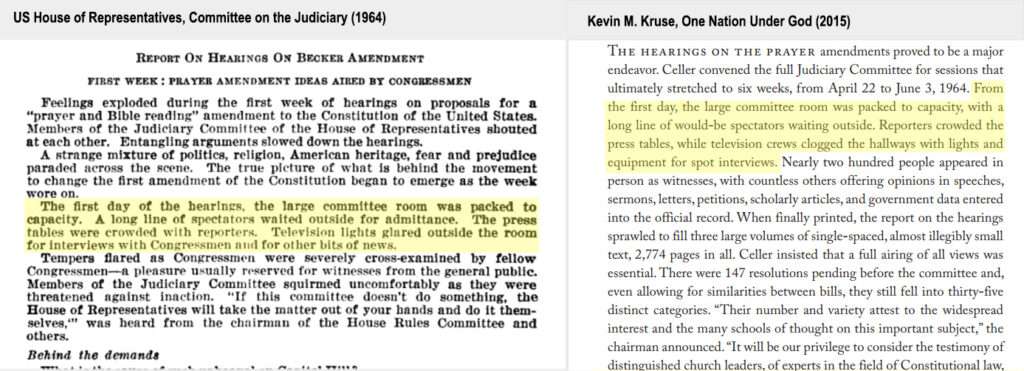

Mangess makes these claims: “I asked Kruse for an explanation of the aforementioned examples from his dissertation. Responding by email, he indicated his ‘intellectual debts to Prof. Bayor and Prof. Sugrue in the text, endnotes and bibliography’ but acknowledged that I had ‘found instances here in which I inartfully or incompletely paraphrased them. Again, thank you for bringing this to my attention and for giving me the opportunity to respond.’ Kruse’s scholarship shows other signs of textual borrowing that are careless at minimum, and not unlike what he accused Clarke of doing in the latter’s master’s thesis. I first encountered similar problems while writing a review of another Kruse book—2015’s One Nation Under God—for an academic journal. The book advances a provocative theory that attributes the modern-day presence of religiosity in American politics to what Kruse labels a ‘Christian libertarian’ assault on the New Deal in the 1940s and ’50s. It also exhibits sourcing patterns that resemble those in his dissertation. Kruse’s narrative caught my attention when he referenced a relatively obscure quotation from Abraham Lincoln about the printing of the first ‘greenback’ paper U.S. currency during the American Civil War. Kruse wrote: ‘Lincoln, aware that the gold supply supporting ‘greenbacks’ was dwindling, joked that a more appropriate motto might be found in the words of the apostle Peter: ‘Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have give I thee.” Compare the textual structure of this passage to the presentation of the same Lincoln quote by an earlier source, a 1956 essay by Elizabeth M. Fowler in The New York Times: ‘But it is reported that President Lincoln, mindful of the dwindling gold supply, said that a more appropriate motto for the greenbacks might be the remark of the Apostle Peter: ‘Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have, I give Thee.” Other elements of Kruse’s 2015 book showed similarities to Fowler’s prose, with only minor changes; in total, the textual commonalities continue for more than a page. Unlike the situation with Bayor and Sugrue, Kruse’s 2015 book does include a footnote with a partial citation to the location of Fowler’s article (although he omits any credit of her by name). In another example from One Nation Under God, Kruse appears to commit the same scholarly sins for which he chastised Clarke. Describing a House Judiciary Committee hearing in the wake of the landmark school prayer case of Engel v. Vitale, Kruse writes: ‘From the first day, the large committee room was packed to capacity, with a long line of would-be spectators waiting outside. Reporters crowded the press tables, while television crews clogged the hallways with lights and equipment for spot interviews.’ Here is how the 1964 committee report described the same events: ‘The first day of the hearings, the large committee room was packed to capacity. A long line of spectators waited outside for admittance. The press tables were crowded with reporters. Television lights glared outside the room for interviews with Congressmen and for other bits of news.’ As with Clarke’s alleged transgressions, Kruse includes a citation to the report in his footnotes. He offers no quotation marks around the borrowed language, and appears to further obscure it with minor cosmetic rearrangements of the report’s text. Do passages such as these qualify as ‘textbook plagiarism,’ as Kruse charged Clarke in 2017, or a simpler form of sloppiness?”

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

In the review Magness referred to in the so-called “academic journal” [Actually something called the “Independent Review” from an organization known as the “Independent Institute.” This is an extremely loose definition of an “academic journal” at the very best.] is here. Again, ignoring the snark and questionable claims, let’s get right to the plagiarism accusations: “The single-page treatment is almost entirely dependent on a cursory reading and rephrasing of another source from the secondary literature. Kruse borrows his account from a 1956 article by New York Times reporter Elizabeth Fowler, citing the piece in a footnote as his lone source. (Elizabeth M. Fowler. In God We Trust. New York Times, July 28, 1956. Kruse’s footnote indicated the date of the piece, but neglects to credit Fowler as the author.) Indeed, several of his own passages appear to have been hastily cribbed from this earlier work. Here, for example, is Kruse:

This article in the right-wing publication Daily Caller says, “Princeton University waited six months to respond to reports of possible plagiarism by a left-wing professor, economics historian Phillip Magness told the Daily Caller on Friday. Magness found signs of ‘possible’ plagiarism in historian Kevin Kruse’s 2015 book, ‘One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America,’ he told the Daily Caller. Magness first contacted Princeton’s Dean of Faculty, Gene Jarrett, and Kruse’s publisher in December pointing to several passages in the book that seemed to align closely with a 1956 New York Times article by reporter Elizabeth Fowler about former President Abraham Lincoln. ‘I did not receive any response or even an acknowledgement from Jarrett’s office,’ Magness told the Daily Caller. Six months later, Magness contacted the university’s Dean of Research, Pablo Debenedetti, on June 7, who said the dean of faculty is responsible for conducting these investigations and forwarded the message to Jarrett’s office. ‘I contacted Princeton directly about these discoveries out of a concern for academic integrity,’ Magness told the Daily Caller before being contacted. ‘It was my hope that they would investigate these issues through the appropriate channels, and my intention [was] to give them an opportunity to do so. Unfortunately, they appear to have been unresponsive to multiple attempts to bring the issues to their attention. That is why I decided to publish my findings in Reason.’ Princeton contacted Magness on Friday and said they take these sorts of allegations ‘very seriously’ and are willing to ‘carefully consider’ the case, according to an email obtained by the Daily Caller. ‘Your email of June 7, 2022, below, to the University’s Dean for Research has been forwarded to the Office of the Dean of the Faculty, as allegations of research misconduct on the part of a member of the Faculty are the concern of this office. We take such allegations very seriously, and we will carefully consider the concerns you have raised,’ Toni Turano, deputy dean of faculty, said, according to the email.”

Dr. Lora Burnett considered these charges in this post. She writes, “The introduction/methodology section of Kevin Kruse’s dissertation includes six sentences that are slightly-altered versions of other authors’ work without including a citation for the original sources, which indicates that those six sentences are probably plagiarized. If there are any other plagiarized passages in Kruse’s work, they will likely come to light in the next few weeks, probably as a result of intense scrutiny by fellow scholars.”

She then discusses plagiarism in general: “Plagiarism is an author’s intentional or unintentional presentation of someone else’s words, arguments, or ideas as the author’s own work. Now, before I go any further, let me note: I didn’t google the definition of plagiarism I presented above. I don’t have a source to cite for it. I didn’t copy it verbatim from another source, nor did I slightly alter another source. Nevertheless, it’s quite probable that my definition of plagiarism closely matches, in whole or in part, someone else’s previously published definition. There’s a non-sinister reason for this similarity: the distinguishing marks of plagiarism I have identified here are ‘common knowledge’ among professional scholars. Statements that constitute ‘common knowledge’ shared by writer and audience don’t require a footnote or reference to an authoritative source. Knowledgeable readers recognize such statements in passing as both true and unoriginal; no footnote expected or required. Here’s an example, a brief passage that communicates common knowledge: ‘In 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered perhaps the most famous piece of American oratory ever preserved in writing, the ‘Gettysburg Address.’ His speech was much shorter than that of the other speakers assembled to dedicate the cemetery for fallen soldiers at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, but Lincoln’s phrasing is indelibly etched into the historical memory of the nation.’ “

“The two sentences above, which I just dashed off as an example for this essay, contain a number of claims that are all true and that are not original to me:

Next she considers specific accusations against Professor Kruse: “In the case of the six sentences highlighted in the Reason article, they do contain some common knowledge — key Black activists have called Atlanta home; Atlanta has long billed itself as ‘the city too busy to hate’; Atlanta has played a central part in Black education in America. Nevertheless, Kruse’s six sentences reproduce not only these well-known facts about Atlanta and the order in which these facts are presented, but also the particular conclusions earlier authors have reached after enumerating these facts. Near-identical phrasing of one sentence or part of a sentence could be a happy accident. However, the near-identical phrasing of these six sentences, presenting the same points in the same order leading to the same conclusion, did not happen by chance. During either the note-taking phase of research or the writing phase of his dissertation, Kruse slightly paraphrased these six sentences from other authors and did not cite the texts in which the original phrasing appears. The intentional or unintentional presentation of someone else’s words as one’s own is plagiarism, so these six sentences are, by definition, plagiarized. Presenting someone else’s words as his own may not have been Kruse’s intention; he may have had a couple of footnotes that got dropped during editing. (This is every historian’s nightmare, but I’m sure it happens, and my surmise is that it may have happened with more frequency with word processing programs twenty-some years ago.) Kruse may have forgotten that his notes were a paraphrase of other authors’ work, rather than a summation of conclusions he reached upon reading that work. The longer the time period between when you take a note and when you use a note, the more likely this is to happen. Again, it’s every historian’s nightmare, but it does occur, and if it happened in this case, it would be a sign that Kruse got careless with his note-taking on the two sources used here. Or, distressing as it may be to think, it’s possible that Kruse wanted to pass off other authors’ reflections on the suitability of Atlanta as a case study as his own reflections. While intention (or lack of it) might reveal a great deal about Kruse’s character during his dissertation days, it’s difficult to impossible to determine his intentions — which is precisely why questions of plagiarism do not hinge upon intentions, but only on the text as presented. TL;DR: There are six plagiarized sentences in Kevin Kruse’s dissertation.”

She also considers the case of the New York Times article: “In one instance, Kruse drew on a New York Times piece, which he cited, to provide a quick overview of discussions regarding putting some sort of phrase acknowledging God on America’s currency, an overview which takes up two paragraphs. As is the case with most history books published by non-academic presses — in this case, Basic Books was Kruse’s publisher for In God We Trust — the authorities, sources, or texts used in any particular paragraph appear in one note at the end of each paragraph. In each of these two paragraphs, Kruse presents information first reported in the New York Times, and at the end of each paragraph he cites the article from which he drew the information. You can find the passages in question in chapter four of Kruse’s book, ‘Pledging Allegiance,’ on pages 112–113. The two notes, one for each paragraph, can be found on page 318. In my judgment as a scholar, there is nothing unusual or untoward about Kruse’s use of this source. I would encourage other scholars to consider the same passage — unlike the author of the Reason piece, I have indicated exactly where you can find these two paragraphs in Kruse’s text. Accurately paraphrasing newspaper articles rather than directly quoting them, and then citing the source of the information, is not plagiarism; it is, rather, the definition of responsible historical practice.”

She tells us, “The same holds true for the last example of ‘problematic’ texts identified in the Reason article. In this example, the author criticizes Kruse for paraphrasing a government report’s description of a meeting and then citing the source, rather than simply reproducing verbatim the government report in quotation marks. The author then asks, ‘Do passages such as these qualify as ‘textbook plagiarism,’ as Kruse charged [Sheriff David] Clarke in 2017, or a simpler form of sloppiness?’ This is a false dichotomy. Kruse’s practice here, paraphrasing a government document and then citing it, is standard and careful historical practice. Clarke, on the other hand, was apparently accused of using passages verbatim but citing them in a way that would indicate he was paraphrasing them, because he did not include quotation marks in his text. ‘I used this text word for word and cited it, but I did not include quotation marks around the verbatim borrowing’ is not the same thing as ‘I reworded this text and cited it as my source.’ The first is either careless or deliberately deceptive (let’s go with careless), and the second is standard and responsible historical scholarship. It’s certainly possible that the author of the Reason piece does not understand standard and responsible historical scholarship and thus is unable to distinguish between unattributed paraphrase, attributed paraphrase, and word-for-word reproduction of a source without proper attribution (quotation marks or block-quoting of the text, and citation).”

In assessing the claims in their totality, she tells us, “The motives of an author who has written a passage flagged as plagiarized have no bearing in determining whether or not the passage in question is in fact plagiarized. Here, again, is the definition of plagiarism: either intentionally or unintentionally borrowing or using the words, arguments, or ideas of another author/text without properly crediting/attributing that source. By that definition, it seems clear to me that six sentences in Kevin Kruse’s dissertation were plagiarized. That is unfortunate and disappointing, and it will doubtless invite extraordinary scrutiny on the rest of Kruse’s work by his colleagues and frenemies alike. … The introduction/methodology section of your dissertation is the last thing you write, but you always put it first. That is, once you have written a serviceable dissertation, which has taken whatever shape it has taken, you go back and describe what factors did and did not influence the shape that it took. Sometimes this happens in your introduction, and sometimes there is a whole chapter dedicated to methodology. In either case, you generally can’t write that section about what your dissertation contains and how it is structured and what influenced your choices until you have actually finished that dissertation and made those choices. So, knowing that the methodology section is generally the last thing a dissertator writes, my general assumption is that it’s the last thing a dissertator wants to get wrong. The hard work of constructing a sustained narrative that is at the same time an argument is done. Describing what is done is the easy part. Exhausting, perhaps, but relatively easy compared to what has already gone before. And in no circumstances would a scholar who has carefully worked to write an original dissertation with all sources appropriately used and cited want to jeopardize that immensely long and difficult work by deliberately misusing two sources in the introduction. If there are no plagiarized sentences in the body of the dissertation, but six plagiarized sentences in the introduction/methodology section, my assumption, based on the evidence at hand, is that the plagiarism was likely unintentional. That doesn’t make it okay. Instead, that means that Kevin Kruse — and all the rest of us, of course — should strive to take as much care in the very finishing stages of our projects as we do over the course of our research. It would be shattering to run a marathon and then trip and fall five yards before the finish line. None of us is immune to mistakes or moments of carelessness. Heaven forbid that a careless error, or hurried notes, or one or two forgotten footnotes, should cause our colleagues to doubt our work. This is the kind of thing that gives historians nightmares, literal nightmares. None of us want this to happen to us, and none of us want it to happen to any other historian.”

Magness tried to respond to Dr. Burnett on Twitter and failed miserably as you can see here. He writes, “The @ldburnett defense of Kevin Kruse’s plagiarism repeatedly asserts that close paraphrasing, using nearly identical wordings without quotation marks, is ‘standard historical practice’ and is therefore permissible. The American Historical Association disagrees.” Then he reproduces this image:

Taken from the Magness tweet

Magness misreads what the AHA has here. Professor Kruse’s paraphrase doesn’t meet the “inadequate” standard, and he cited the source.

The Daily Princetonian, the campus newspaper of Princeton University, has a pretty good story about this case. “Kruse expressed ‘surprise’ at the allegations and attributed the lack of citations in one instance to an inadvertent oversight. ‘While I indicated my intellectual debts to Prof. Bayor elsewhere in the text, endnotes and bibliography of the dissertation, I was surprised to see that there was an instance in the introduction in which I failed to do so properly,’ Kruse wrote in an email to The Daily Princetonian. Bayor himself expressed skepticism around the allegations in an email to the ‘Prince,’ attributing Kruse’s alleged missteps to ‘sloppy notetaking’ and suggesting that the recently surfaced allegations are politically motivated. Kruse holds a reputation as a renowned left-leaning professor and ‘history’s attack dog,’ as he was once termed by The Chronicle of Higher Education, with a long track record of taking to platforms like Twitter to correct common misinterpretations of American history by conservative and other political commentators. As a scholar of 20th-century American history, Kruse has written books on religious nationalism, urban and suburban history, and the Civil Rights Movement. He has served as a professor at the University since 2000, most recently teaching a lecture on U.S. history from 1920 to 1974 as well as a seminar on the political history of civil rights.”

The article tells us, “Several conservative critics, including Princeton University student Abigail Anthony ’23, have argued that the University’s seeming inaction on Kruse’s alleged plagiarism stands in stark contrast to what some have criticized as the unjust termination of former classics professor Joshua Katz this past May. During the spring of 2022, the University dismissed Katz following an internal finding that Katz ‘misrepresented facts’ during a 2018 investigation into a relationship he had with a student, discouraged the alumna from participating in said investigation, and tried to prevent her from seeking mental health care when she was a student, according to the University. His defenders have claimed the dismissal was retribution for a controversial column Katz wrote for Quillette in July 2020 in which he opposed a faculty letter on racial equity and labeled a now-inactive student group, the Black Justice League, a ‘small local terrorist organization.’ When asked by the ‘Prince’ whether the University is investigating the plagiarism allegations against Kruse, University Spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss said in an email that administrators are currently ‘reviewing’ the claims. ‘The University is committed to the highest ethical and scholarly standards, and thus takes allegations of research misconduct very seriously. We are carefully reviewing the concerns that have been shared with the University, and will handle them in accordance with University policy,’ Hotchkiss wrote.”

The article continues, “Magness, who works as a researcher at the libertarian think tank American Institute for Economic Research, wrote in an email to the ‘Prince’ that he discovered the alleged instances of plagiarism while reviewing Kruse’s book ‘One Nation Under God’ for an academic journal. In the original Reason article as well as a slate of related blog posts, Magness identified two particular texts from which Kruse allegedly plagiarized: Bayor’s ‘Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta’ as well as ‘The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit’ (published in 1996), a book written by Thomas Sugrue, a historian and Julius Silver Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and History at New York University. … In response to allegations that Kruse plagiarized from his book, Bayor questioned whether such claims even merited discussion. ‘It looks to me like very sloppy notetaking which can be fixed with an endnote. I did not see the dissertation but did read his book on [the] Atlanta suburbs and found it to be a sound and important history,’ Bayor wrote in an email to the ‘Prince.’ He argued that Magness’s allegations are made in bad faith. ‘I don’t approve of politically motivated attacks on good scholarship whether it comes from the right or left, and I believe this scrutiny of Kruse’s work is just that. There is not a story here,’ Bayor added.”

According to the article, “Since penning the Reason article, Magness told the ‘Prince’ that he has unearthed additional evidence of possible plagiarism in Kruse’s book. ‘I have since found several additional passages in One Nation Under God that closely resemble the wordings and argument structures of other previously published books,’ Magness wrote to the ‘Prince.’ ‘These examples include citations in the footnotes, but they also generally lack the requisite quotation marks to indicate that certain phrases and sentences are borrowed from other authors.’ Still, Magness said he sees these other examples as less ‘severe’ than the first. ‘Although these examples are not as severe as the passages from Kruse’s dissertation (which entailed several near-verbatim sentences without any citations or quotation marks to indicate their source), they suggest a wider pattern of possible problems in this book,’ he wrote. Soon after discovering these alleged instances of plagiarism, Magness said he notified the University about his concerns but never received a response. He claims the University only began to address his concerns after they became public in June. ‘I received a response a few days after my Reason article was published,’ he wrote, ‘indicating that they had begun an investigation. I have since provided the niversity with details regarding additional textual irregularities as they have come to light.’ “

We also learn, “The University’s ‘Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities’ directs all University members to observe ‘basic honesty in one’s work, words, ideas, and actions [as] a principle to which all members of the community are required to subscribe.’ In an email to the ‘Prince,’ Hotchkiss wrote that the University had overlooked Magness’s original email for a simple reason: it never reached any administrators. ‘On December 6, 2021, Phillip Magness sent a message to a generic email address monitored by the Office of the Dean of the Faculty. The email was overlooked, and the appropriate University officials did not learn of his allegations until this month,’ Hotchkiss said in a statement first sent to the ‘Prince’ in June. The news of Kruse allegedly plagiarizing material in his written work has prompted an outcry and calls for accountability among several notable detractors, including right-wing political commentator Dinesh D’Souza and Senator Ted Cruz ’92 (R-Texas), who have publicly called on the University to initiate a full-fledged investigation into the allegations.”

Finally, the article says, “Princeton history professor David Bell, who serves as a committee member at the Center for Collaborative History alongside Kruse, offered his own perspective on the matter. He argued that the severity of plagiarism offenses exists along a continuum, and that Magness’s charges of plagiarism fall short of considering these nuances. Bell noted that his opinion does not represent the views of the history department, the Shelby Cullom Davis Center, or the University. ‘While plagiarism is always wrong, there are, obviously, many different degrees of plagiarism. There is a huge difference, for instance, between passing off someone else’s entire article as one’s own, and copying a few sentences,’ wrote Bell in an email to the ‘Prince.’ ‘In the latter case, it matters whether the sentences in question are crucial to the work or not—whether or not they represent a theft of key ideas or evidence. What Magness uncovered was the copying of a few pieces of felicitous, but essentially incidental prose. Magness is wrong to charge Kruse with plagiarizing a ‘key passage’ of his dissertation. This should be kept in mind when asking what consequences Kruse should face,’ he wrote.”

The Chronicle of Higher Education also has an article on this situation. “Both of the passages taken from Bayor and Sugrue appear early in Kruse’s dissertation as he’s explaining what he believes his research adds to the field. There are no quotation marks or citations of the authors (though both are cited later in the dissertation). Bayor told me he doesn’t consider what Kruse did, at least with regard to the sentences from his book, plagiarism. ‘There are a few introductory sentences he used that are almost verbatim, and they’re not important in my book,’ he said. ‘I attributed it to sloppy note-taking.’ (I contacted Sugrue, a historian at New York University, but haven’t heard back.) It might be sloppy note-taking, a momentary lapse by a scholar hastily putting the final touches on a dissertation that was years in the making. Those sentences were either excised or revised in Kruse’s 2005 book, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, which is based on his dissertation. And, as several defenders have noted, we’re talking about a few sentences in a heavily footnoted 600-page dissertation that draws on a wide array of primary and secondary sources.”

The article also says, “Still, what Kruse did in those instances is, by almost any definition, plagiarism. And it is certainly plagiarism under Princeton’s guidelines, which specifically say that sloppiness is not an acceptable excuse. In an emailed statement, Michael Hotchkiss, a Princeton spokesperson, writes that the university is ‘committed to the highest ethical and scholarly standards’ and that it’s ‘carefully reviewing the concerns that have been shared with the university, and will handle them in accordance with university policy.’ In a brief interview, Kruse declined to discuss the passages in question or to say what he thinks of Magness’s motivation, but he acknowledged failing to credit Bayor and Sugrue. ‘While I tried very hard in my dissertation to give full and proper acknowledgment to all my sources, I clearly fell short in those instances,’ he told me. ‘I’ve spoken with Professor Bayor and Professor Sugrue, and I’m grateful to have such kind and generous intellectual mentors.’ “

As Professor Brooks Simpson has said, we need to look at the merits of the actual accusations, not whether or not Magness is a bad actor. Princeton University and Cornell University are both conducting reviews, and they will determine officially whether there was plagiarism, whether it was more likely the result of misconduct or simply honest error, and what, if any, punishment will be applied. We will await the results.

Continue reading...

Magness continues, “The similarities do not stop there. In outlining the background for his study, Bayor provides a long list of Atlanta’s famous African-American residents: ‘At one time or another such notables as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond lived within its borders.’ Kruse’s dissertation repeats the same list, subject only to a minor reorganization of the text: ‘Central figures in civil rights history—such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King, Sr. and Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond—have lived inside its limits at one time or another.’ A few sentences later, Bayor begins to summarize his book’s thesis, writing ‘While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe Atlanta is unique in regard to the impact of race.’ Compare that to how Kruse lays out his dissertation’s thesis, which holds that Atlanta’s experience may be representative of other southern cities in the era of segregation: ‘While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe it is unique in regard to its struggles over race and rights.’ The only difference in this case appears to be a cosmetic change of the last few words.”

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

Magness also tells us, “Kruse’s dissertation contains other passages with striking similarities to previously published works. Consider this passage from historian Thomas Sugrue’s 1996 book The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit: ‘The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I have chosen a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of generalizations such as discrimination, deindustrialization, and racism.’ Kruse uses almost identical language in his dissertation, although he shifts its location from Detroit to Atlanta: ‘The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I chose to conduct a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of broad generalizations—racism, discrimination, backlash, ‘white flight.” “

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

According to Magness, “Unlike Clarke, whose masters’ thesis merely failed to place the cribbed but cited texts in quotation marks, the suspect passages in Kruse’s dissertation offer no accompanying footnote to Bayor or Sugrue’s works. His first acknowledgement of Bayor comes several pages later, in a section on the historiography around Atlanta’s civil rights struggles. Here Kruse calls the 1996 book the ‘most impressive work on Atlanta’s race relations’ to date, although he then dings it for focusing ‘solely on the top levels of society.’ (‘Bayor’s work fails to go any deeper,’ Kruse adds. ‘I wanted to show the rest.’) The first reference to Sugrue is an unrelated footnote some 90 pages later in the dissertation.”

Mangess makes these claims: “I asked Kruse for an explanation of the aforementioned examples from his dissertation. Responding by email, he indicated his ‘intellectual debts to Prof. Bayor and Prof. Sugrue in the text, endnotes and bibliography’ but acknowledged that I had ‘found instances here in which I inartfully or incompletely paraphrased them. Again, thank you for bringing this to my attention and for giving me the opportunity to respond.’ Kruse’s scholarship shows other signs of textual borrowing that are careless at minimum, and not unlike what he accused Clarke of doing in the latter’s master’s thesis. I first encountered similar problems while writing a review of another Kruse book—2015’s One Nation Under God—for an academic journal. The book advances a provocative theory that attributes the modern-day presence of religiosity in American politics to what Kruse labels a ‘Christian libertarian’ assault on the New Deal in the 1940s and ’50s. It also exhibits sourcing patterns that resemble those in his dissertation. Kruse’s narrative caught my attention when he referenced a relatively obscure quotation from Abraham Lincoln about the printing of the first ‘greenback’ paper U.S. currency during the American Civil War. Kruse wrote: ‘Lincoln, aware that the gold supply supporting ‘greenbacks’ was dwindling, joked that a more appropriate motto might be found in the words of the apostle Peter: ‘Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have give I thee.” Compare the textual structure of this passage to the presentation of the same Lincoln quote by an earlier source, a 1956 essay by Elizabeth M. Fowler in The New York Times: ‘But it is reported that President Lincoln, mindful of the dwindling gold supply, said that a more appropriate motto for the greenbacks might be the remark of the Apostle Peter: ‘Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have, I give Thee.” Other elements of Kruse’s 2015 book showed similarities to Fowler’s prose, with only minor changes; in total, the textual commonalities continue for more than a page. Unlike the situation with Bayor and Sugrue, Kruse’s 2015 book does include a footnote with a partial citation to the location of Fowler’s article (although he omits any credit of her by name). In another example from One Nation Under God, Kruse appears to commit the same scholarly sins for which he chastised Clarke. Describing a House Judiciary Committee hearing in the wake of the landmark school prayer case of Engel v. Vitale, Kruse writes: ‘From the first day, the large committee room was packed to capacity, with a long line of would-be spectators waiting outside. Reporters crowded the press tables, while television crews clogged the hallways with lights and equipment for spot interviews.’ Here is how the 1964 committee report described the same events: ‘The first day of the hearings, the large committee room was packed to capacity. A long line of spectators waited outside for admittance. The press tables were crowded with reporters. Television lights glared outside the room for interviews with Congressmen and for other bits of news.’ As with Clarke’s alleged transgressions, Kruse includes a citation to the report in his footnotes. He offers no quotation marks around the borrowed language, and appears to further obscure it with minor cosmetic rearrangements of the report’s text. Do passages such as these qualify as ‘textbook plagiarism,’ as Kruse charged Clarke in 2017, or a simpler form of sloppiness?”

Image by Phillip Magness taken from the article

In the review Magness referred to in the so-called “academic journal” [Actually something called the “Independent Review” from an organization known as the “Independent Institute.” This is an extremely loose definition of an “academic journal” at the very best.] is here. Again, ignoring the snark and questionable claims, let’s get right to the plagiarism accusations: “The single-page treatment is almost entirely dependent on a cursory reading and rephrasing of another source from the secondary literature. Kruse borrows his account from a 1956 article by New York Times reporter Elizabeth Fowler, citing the piece in a footnote as his lone source. (Elizabeth M. Fowler. In God We Trust. New York Times, July 28, 1956. Kruse’s footnote indicated the date of the piece, but neglects to credit Fowler as the author.) Indeed, several of his own passages appear to have been hastily cribbed from this earlier work. Here, for example, is Kruse:

“And Fowler’s original:“Lincoln, aware that the gold supply supporting “greenbacks” was dwindling, joked that a more appropriate motto might be found in the words of the apostle Peter: “Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have give I thee.”” (p. 112)

“Kruse again:“But it is reported that President Lincoln, mindful of the dwindling gold supply, said that a more appropriate motto for the greenbacks might be the remark of the Apostle Peter: “Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have, I give Thee.””

“And Fowler’s original:“It soon appeared, on bronze 2¢ pieces, in 1864.” (p. 112)

“Kruse again:“It first appeared on the bronze two-cent piece of 1864.”

“And Fowler’s original:“In 1883 the motto was removed from the nickel and would not return for another fifty-five years.” (p. 112)

“These and other awkwardly close paraphrases of Fowler’s article fall far short of the scrupulous consideration one might reasonably expect from a serious scholarly work.”“In fact, in 1883 it was removed from the five-cent piece, not to reappear until 1938.”

This article in the right-wing publication Daily Caller says, “Princeton University waited six months to respond to reports of possible plagiarism by a left-wing professor, economics historian Phillip Magness told the Daily Caller on Friday. Magness found signs of ‘possible’ plagiarism in historian Kevin Kruse’s 2015 book, ‘One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America,’ he told the Daily Caller. Magness first contacted Princeton’s Dean of Faculty, Gene Jarrett, and Kruse’s publisher in December pointing to several passages in the book that seemed to align closely with a 1956 New York Times article by reporter Elizabeth Fowler about former President Abraham Lincoln. ‘I did not receive any response or even an acknowledgement from Jarrett’s office,’ Magness told the Daily Caller. Six months later, Magness contacted the university’s Dean of Research, Pablo Debenedetti, on June 7, who said the dean of faculty is responsible for conducting these investigations and forwarded the message to Jarrett’s office. ‘I contacted Princeton directly about these discoveries out of a concern for academic integrity,’ Magness told the Daily Caller before being contacted. ‘It was my hope that they would investigate these issues through the appropriate channels, and my intention [was] to give them an opportunity to do so. Unfortunately, they appear to have been unresponsive to multiple attempts to bring the issues to their attention. That is why I decided to publish my findings in Reason.’ Princeton contacted Magness on Friday and said they take these sorts of allegations ‘very seriously’ and are willing to ‘carefully consider’ the case, according to an email obtained by the Daily Caller. ‘Your email of June 7, 2022, below, to the University’s Dean for Research has been forwarded to the Office of the Dean of the Faculty, as allegations of research misconduct on the part of a member of the Faculty are the concern of this office. We take such allegations very seriously, and we will carefully consider the concerns you have raised,’ Toni Turano, deputy dean of faculty, said, according to the email.”

Dr. Lora Burnett considered these charges in this post. She writes, “The introduction/methodology section of Kevin Kruse’s dissertation includes six sentences that are slightly-altered versions of other authors’ work without including a citation for the original sources, which indicates that those six sentences are probably plagiarized. If there are any other plagiarized passages in Kruse’s work, they will likely come to light in the next few weeks, probably as a result of intense scrutiny by fellow scholars.”

She then discusses plagiarism in general: “Plagiarism is an author’s intentional or unintentional presentation of someone else’s words, arguments, or ideas as the author’s own work. Now, before I go any further, let me note: I didn’t google the definition of plagiarism I presented above. I don’t have a source to cite for it. I didn’t copy it verbatim from another source, nor did I slightly alter another source. Nevertheless, it’s quite probable that my definition of plagiarism closely matches, in whole or in part, someone else’s previously published definition. There’s a non-sinister reason for this similarity: the distinguishing marks of plagiarism I have identified here are ‘common knowledge’ among professional scholars. Statements that constitute ‘common knowledge’ shared by writer and audience don’t require a footnote or reference to an authoritative source. Knowledgeable readers recognize such statements in passing as both true and unoriginal; no footnote expected or required. Here’s an example, a brief passage that communicates common knowledge: ‘In 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered perhaps the most famous piece of American oratory ever preserved in writing, the ‘Gettysburg Address.’ His speech was much shorter than that of the other speakers assembled to dedicate the cemetery for fallen soldiers at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, but Lincoln’s phrasing is indelibly etched into the historical memory of the nation.’ “

“The two sentences above, which I just dashed off as an example for this essay, contain a number of claims that are all true and that are not original to me:

“None of the above claims require a footnote documenting supporting evidence; they are all common knowledge. The last claim — these words are still important today — could be strengthened, if it were in doubt, by two or three supporting examples of recent references to Lincoln’s words by American authors or politicians. But that supporting evidence is not necessary, because the claim itself is hardly in dispute. It is entirely possible that several authors before me have introduced a discussion of the Gettysburg address in two sentences that use these same claims in the same order. That is, my two sentences about Lincoln’s speech, without being either copied or paraphrased from another source, may still be completely unoriginal in content and style. TL;DR: Similar phrasing and structure between two texts does not always indicate an unattributed borrowing; such similarities can indicate that both texts are drawing from a common set of established facts or a common store of knowledge. What is considered ‘common knowledge’ varies from field to field. Generally, authors in any field can reasonably expect that their intended audience has enough background knowledge of the subject, at least collectively, to distinguish between what is common knowledge and what is an arguable interpretation or an interpretation or claim that requires supporting evidence or reference to other authorities besides the author.”Abraham Lincoln delivered an address in 1863 at a cemetery dedication in Gettysburg, PA.

Abraham Lincoln’s speech was shorter than other speeches delivered that day

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech is very famous.

Abraham Lincoln’s words in that speech are still important to Americans today.

Next she considers specific accusations against Professor Kruse: “In the case of the six sentences highlighted in the Reason article, they do contain some common knowledge — key Black activists have called Atlanta home; Atlanta has long billed itself as ‘the city too busy to hate’; Atlanta has played a central part in Black education in America. Nevertheless, Kruse’s six sentences reproduce not only these well-known facts about Atlanta and the order in which these facts are presented, but also the particular conclusions earlier authors have reached after enumerating these facts. Near-identical phrasing of one sentence or part of a sentence could be a happy accident. However, the near-identical phrasing of these six sentences, presenting the same points in the same order leading to the same conclusion, did not happen by chance. During either the note-taking phase of research or the writing phase of his dissertation, Kruse slightly paraphrased these six sentences from other authors and did not cite the texts in which the original phrasing appears. The intentional or unintentional presentation of someone else’s words as one’s own is plagiarism, so these six sentences are, by definition, plagiarized. Presenting someone else’s words as his own may not have been Kruse’s intention; he may have had a couple of footnotes that got dropped during editing. (This is every historian’s nightmare, but I’m sure it happens, and my surmise is that it may have happened with more frequency with word processing programs twenty-some years ago.) Kruse may have forgotten that his notes were a paraphrase of other authors’ work, rather than a summation of conclusions he reached upon reading that work. The longer the time period between when you take a note and when you use a note, the more likely this is to happen. Again, it’s every historian’s nightmare, but it does occur, and if it happened in this case, it would be a sign that Kruse got careless with his note-taking on the two sources used here. Or, distressing as it may be to think, it’s possible that Kruse wanted to pass off other authors’ reflections on the suitability of Atlanta as a case study as his own reflections. While intention (or lack of it) might reveal a great deal about Kruse’s character during his dissertation days, it’s difficult to impossible to determine his intentions — which is precisely why questions of plagiarism do not hinge upon intentions, but only on the text as presented. TL;DR: There are six plagiarized sentences in Kevin Kruse’s dissertation.”

She also considers the case of the New York Times article: “In one instance, Kruse drew on a New York Times piece, which he cited, to provide a quick overview of discussions regarding putting some sort of phrase acknowledging God on America’s currency, an overview which takes up two paragraphs. As is the case with most history books published by non-academic presses — in this case, Basic Books was Kruse’s publisher for In God We Trust — the authorities, sources, or texts used in any particular paragraph appear in one note at the end of each paragraph. In each of these two paragraphs, Kruse presents information first reported in the New York Times, and at the end of each paragraph he cites the article from which he drew the information. You can find the passages in question in chapter four of Kruse’s book, ‘Pledging Allegiance,’ on pages 112–113. The two notes, one for each paragraph, can be found on page 318. In my judgment as a scholar, there is nothing unusual or untoward about Kruse’s use of this source. I would encourage other scholars to consider the same passage — unlike the author of the Reason piece, I have indicated exactly where you can find these two paragraphs in Kruse’s text. Accurately paraphrasing newspaper articles rather than directly quoting them, and then citing the source of the information, is not plagiarism; it is, rather, the definition of responsible historical practice.”

She tells us, “The same holds true for the last example of ‘problematic’ texts identified in the Reason article. In this example, the author criticizes Kruse for paraphrasing a government report’s description of a meeting and then citing the source, rather than simply reproducing verbatim the government report in quotation marks. The author then asks, ‘Do passages such as these qualify as ‘textbook plagiarism,’ as Kruse charged [Sheriff David] Clarke in 2017, or a simpler form of sloppiness?’ This is a false dichotomy. Kruse’s practice here, paraphrasing a government document and then citing it, is standard and careful historical practice. Clarke, on the other hand, was apparently accused of using passages verbatim but citing them in a way that would indicate he was paraphrasing them, because he did not include quotation marks in his text. ‘I used this text word for word and cited it, but I did not include quotation marks around the verbatim borrowing’ is not the same thing as ‘I reworded this text and cited it as my source.’ The first is either careless or deliberately deceptive (let’s go with careless), and the second is standard and responsible historical scholarship. It’s certainly possible that the author of the Reason piece does not understand standard and responsible historical scholarship and thus is unable to distinguish between unattributed paraphrase, attributed paraphrase, and word-for-word reproduction of a source without proper attribution (quotation marks or block-quoting of the text, and citation).”

In assessing the claims in their totality, she tells us, “The motives of an author who has written a passage flagged as plagiarized have no bearing in determining whether or not the passage in question is in fact plagiarized. Here, again, is the definition of plagiarism: either intentionally or unintentionally borrowing or using the words, arguments, or ideas of another author/text without properly crediting/attributing that source. By that definition, it seems clear to me that six sentences in Kevin Kruse’s dissertation were plagiarized. That is unfortunate and disappointing, and it will doubtless invite extraordinary scrutiny on the rest of Kruse’s work by his colleagues and frenemies alike. … The introduction/methodology section of your dissertation is the last thing you write, but you always put it first. That is, once you have written a serviceable dissertation, which has taken whatever shape it has taken, you go back and describe what factors did and did not influence the shape that it took. Sometimes this happens in your introduction, and sometimes there is a whole chapter dedicated to methodology. In either case, you generally can’t write that section about what your dissertation contains and how it is structured and what influenced your choices until you have actually finished that dissertation and made those choices. So, knowing that the methodology section is generally the last thing a dissertator writes, my general assumption is that it’s the last thing a dissertator wants to get wrong. The hard work of constructing a sustained narrative that is at the same time an argument is done. Describing what is done is the easy part. Exhausting, perhaps, but relatively easy compared to what has already gone before. And in no circumstances would a scholar who has carefully worked to write an original dissertation with all sources appropriately used and cited want to jeopardize that immensely long and difficult work by deliberately misusing two sources in the introduction. If there are no plagiarized sentences in the body of the dissertation, but six plagiarized sentences in the introduction/methodology section, my assumption, based on the evidence at hand, is that the plagiarism was likely unintentional. That doesn’t make it okay. Instead, that means that Kevin Kruse — and all the rest of us, of course — should strive to take as much care in the very finishing stages of our projects as we do over the course of our research. It would be shattering to run a marathon and then trip and fall five yards before the finish line. None of us is immune to mistakes or moments of carelessness. Heaven forbid that a careless error, or hurried notes, or one or two forgotten footnotes, should cause our colleagues to doubt our work. This is the kind of thing that gives historians nightmares, literal nightmares. None of us want this to happen to us, and none of us want it to happen to any other historian.”

Magness tried to respond to Dr. Burnett on Twitter and failed miserably as you can see here. He writes, “The @ldburnett defense of Kevin Kruse’s plagiarism repeatedly asserts that close paraphrasing, using nearly identical wordings without quotation marks, is ‘standard historical practice’ and is therefore permissible. The American Historical Association disagrees.” Then he reproduces this image:

Taken from the Magness tweet

Magness misreads what the AHA has here. Professor Kruse’s paraphrase doesn’t meet the “inadequate” standard, and he cited the source.

The Daily Princetonian, the campus newspaper of Princeton University, has a pretty good story about this case. “Kruse expressed ‘surprise’ at the allegations and attributed the lack of citations in one instance to an inadvertent oversight. ‘While I indicated my intellectual debts to Prof. Bayor elsewhere in the text, endnotes and bibliography of the dissertation, I was surprised to see that there was an instance in the introduction in which I failed to do so properly,’ Kruse wrote in an email to The Daily Princetonian. Bayor himself expressed skepticism around the allegations in an email to the ‘Prince,’ attributing Kruse’s alleged missteps to ‘sloppy notetaking’ and suggesting that the recently surfaced allegations are politically motivated. Kruse holds a reputation as a renowned left-leaning professor and ‘history’s attack dog,’ as he was once termed by The Chronicle of Higher Education, with a long track record of taking to platforms like Twitter to correct common misinterpretations of American history by conservative and other political commentators. As a scholar of 20th-century American history, Kruse has written books on religious nationalism, urban and suburban history, and the Civil Rights Movement. He has served as a professor at the University since 2000, most recently teaching a lecture on U.S. history from 1920 to 1974 as well as a seminar on the political history of civil rights.”

The article tells us, “Several conservative critics, including Princeton University student Abigail Anthony ’23, have argued that the University’s seeming inaction on Kruse’s alleged plagiarism stands in stark contrast to what some have criticized as the unjust termination of former classics professor Joshua Katz this past May. During the spring of 2022, the University dismissed Katz following an internal finding that Katz ‘misrepresented facts’ during a 2018 investigation into a relationship he had with a student, discouraged the alumna from participating in said investigation, and tried to prevent her from seeking mental health care when she was a student, according to the University. His defenders have claimed the dismissal was retribution for a controversial column Katz wrote for Quillette in July 2020 in which he opposed a faculty letter on racial equity and labeled a now-inactive student group, the Black Justice League, a ‘small local terrorist organization.’ When asked by the ‘Prince’ whether the University is investigating the plagiarism allegations against Kruse, University Spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss said in an email that administrators are currently ‘reviewing’ the claims. ‘The University is committed to the highest ethical and scholarly standards, and thus takes allegations of research misconduct very seriously. We are carefully reviewing the concerns that have been shared with the University, and will handle them in accordance with University policy,’ Hotchkiss wrote.”

The article continues, “Magness, who works as a researcher at the libertarian think tank American Institute for Economic Research, wrote in an email to the ‘Prince’ that he discovered the alleged instances of plagiarism while reviewing Kruse’s book ‘One Nation Under God’ for an academic journal. In the original Reason article as well as a slate of related blog posts, Magness identified two particular texts from which Kruse allegedly plagiarized: Bayor’s ‘Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta’ as well as ‘The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit’ (published in 1996), a book written by Thomas Sugrue, a historian and Julius Silver Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and History at New York University. … In response to allegations that Kruse plagiarized from his book, Bayor questioned whether such claims even merited discussion. ‘It looks to me like very sloppy notetaking which can be fixed with an endnote. I did not see the dissertation but did read his book on [the] Atlanta suburbs and found it to be a sound and important history,’ Bayor wrote in an email to the ‘Prince.’ He argued that Magness’s allegations are made in bad faith. ‘I don’t approve of politically motivated attacks on good scholarship whether it comes from the right or left, and I believe this scrutiny of Kruse’s work is just that. There is not a story here,’ Bayor added.”

According to the article, “Since penning the Reason article, Magness told the ‘Prince’ that he has unearthed additional evidence of possible plagiarism in Kruse’s book. ‘I have since found several additional passages in One Nation Under God that closely resemble the wordings and argument structures of other previously published books,’ Magness wrote to the ‘Prince.’ ‘These examples include citations in the footnotes, but they also generally lack the requisite quotation marks to indicate that certain phrases and sentences are borrowed from other authors.’ Still, Magness said he sees these other examples as less ‘severe’ than the first. ‘Although these examples are not as severe as the passages from Kruse’s dissertation (which entailed several near-verbatim sentences without any citations or quotation marks to indicate their source), they suggest a wider pattern of possible problems in this book,’ he wrote. Soon after discovering these alleged instances of plagiarism, Magness said he notified the University about his concerns but never received a response. He claims the University only began to address his concerns after they became public in June. ‘I received a response a few days after my Reason article was published,’ he wrote, ‘indicating that they had begun an investigation. I have since provided the niversity with details regarding additional textual irregularities as they have come to light.’ “

We also learn, “The University’s ‘Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities’ directs all University members to observe ‘basic honesty in one’s work, words, ideas, and actions [as] a principle to which all members of the community are required to subscribe.’ In an email to the ‘Prince,’ Hotchkiss wrote that the University had overlooked Magness’s original email for a simple reason: it never reached any administrators. ‘On December 6, 2021, Phillip Magness sent a message to a generic email address monitored by the Office of the Dean of the Faculty. The email was overlooked, and the appropriate University officials did not learn of his allegations until this month,’ Hotchkiss said in a statement first sent to the ‘Prince’ in June. The news of Kruse allegedly plagiarizing material in his written work has prompted an outcry and calls for accountability among several notable detractors, including right-wing political commentator Dinesh D’Souza and Senator Ted Cruz ’92 (R-Texas), who have publicly called on the University to initiate a full-fledged investigation into the allegations.”

Finally, the article says, “Princeton history professor David Bell, who serves as a committee member at the Center for Collaborative History alongside Kruse, offered his own perspective on the matter. He argued that the severity of plagiarism offenses exists along a continuum, and that Magness’s charges of plagiarism fall short of considering these nuances. Bell noted that his opinion does not represent the views of the history department, the Shelby Cullom Davis Center, or the University. ‘While plagiarism is always wrong, there are, obviously, many different degrees of plagiarism. There is a huge difference, for instance, between passing off someone else’s entire article as one’s own, and copying a few sentences,’ wrote Bell in an email to the ‘Prince.’ ‘In the latter case, it matters whether the sentences in question are crucial to the work or not—whether or not they represent a theft of key ideas or evidence. What Magness uncovered was the copying of a few pieces of felicitous, but essentially incidental prose. Magness is wrong to charge Kruse with plagiarizing a ‘key passage’ of his dissertation. This should be kept in mind when asking what consequences Kruse should face,’ he wrote.”

The Chronicle of Higher Education also has an article on this situation. “Both of the passages taken from Bayor and Sugrue appear early in Kruse’s dissertation as he’s explaining what he believes his research adds to the field. There are no quotation marks or citations of the authors (though both are cited later in the dissertation). Bayor told me he doesn’t consider what Kruse did, at least with regard to the sentences from his book, plagiarism. ‘There are a few introductory sentences he used that are almost verbatim, and they’re not important in my book,’ he said. ‘I attributed it to sloppy note-taking.’ (I contacted Sugrue, a historian at New York University, but haven’t heard back.) It might be sloppy note-taking, a momentary lapse by a scholar hastily putting the final touches on a dissertation that was years in the making. Those sentences were either excised or revised in Kruse’s 2005 book, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, which is based on his dissertation. And, as several defenders have noted, we’re talking about a few sentences in a heavily footnoted 600-page dissertation that draws on a wide array of primary and secondary sources.”

The article also says, “Still, what Kruse did in those instances is, by almost any definition, plagiarism. And it is certainly plagiarism under Princeton’s guidelines, which specifically say that sloppiness is not an acceptable excuse. In an emailed statement, Michael Hotchkiss, a Princeton spokesperson, writes that the university is ‘committed to the highest ethical and scholarly standards’ and that it’s ‘carefully reviewing the concerns that have been shared with the university, and will handle them in accordance with university policy.’ In a brief interview, Kruse declined to discuss the passages in question or to say what he thinks of Magness’s motivation, but he acknowledged failing to credit Bayor and Sugrue. ‘While I tried very hard in my dissertation to give full and proper acknowledgment to all my sources, I clearly fell short in those instances,’ he told me. ‘I’ve spoken with Professor Bayor and Professor Sugrue, and I’m grateful to have such kind and generous intellectual mentors.’ “

As Professor Brooks Simpson has said, we need to look at the merits of the actual accusations, not whether or not Magness is a bad actor. Princeton University and Cornell University are both conducting reviews, and they will determine officially whether there was plagiarism, whether it was more likely the result of misconduct or simply honest error, and what, if any, punishment will be applied. We will await the results.

Continue reading...